TFN Talks with Vagif Rakhmanov

TFN Talks sat down to talk about art, life and culture with Vagif Rakhmanov, renowned Azerbaijani sculptor and graphic artist, Honored Artist of Kazakhstan (1981), People’s artist of Kazakhstan (2007) and recepient of a Lifetime Achievement Award in Arts and Culture awarded by the Consulate of Azerbaijan to Kazakhstan. In March of 2018 Rakhmanov was awarded the President’s Highest Honor Medal by the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev for his contribution in sculpture to the arts and culture of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Where were you born and at what age did you first start sculpting or having the dreams of becoming a sculptor? Was your family supportive of your career choice?

I was born in Baku, Azerbajian in 1941. When I was four and a half years old, one of my older sisters was married to a sculptor, the first sculptor in the family to have a higher education in the arts, he studied in Moscow, which was prestigious at the time. His name was Fuat Abdurakhmanov. He gave me a piece of brown plasticine and said “try to make something”. I said “thank you” and that was it. I started making tanks, planes, cars. There were no toys, no money, it was WWII and I made plasticine toys for myself. I wanted to invite friends over to play but there was no one around, so I would sit near the window in Baku and play with my plasticine toys, which I sculpted. One of my sisters (I had nine siblings), was an archictect and one was a visual artist, a painter. Maral, the oldest sister painted and drew graphics, she became quite famous over the years, the most famous female painter in the country, and I observed her at her craft. My family never really interfered in what I was doing in sculpture, they showed support.

Vagif Rakhmanov , age 6

Can you tell us about where you studied sculpture in your formative years and what does it take in terms of education for someone to be considered ready for a career in sculpture?

In grade eight I stopped understanding mathematics at school, I was terrible. But I was constantly sculpting and making figures. One day I went to the cinema and saw the original ‘Tarzan’. I came home and sculpted Tarzan, an exact copy of what I saw on the screen. My sister saw it, hit me really hard, broke the little sculpture and told me to study mathematics. Everyone was very busy, no one really had time for my education. My father was abducted and murdered by the Russian Red Army and my mother only had time for trying to feed the ten of us. She would travel 35 kilometres every day into the villages to find food. I was left alone and I read a lot of books. At the age of six I could already speak fluent Russian, as well as my native tongue, Azeri. I had only three friends, three local boys, a Russian, Tatar and Polish. I was in love with the Caspian Sea and I dreamt of being a sailor. In grade eight my mathematics were so bad the school decided to expel me, so they asked me to leave or I would get kicked out. I said “ok”, came back to my sculptures and then went to enrol in an elite Marine Military College in Baku. I said “ I want to be a sailor”. They asked me for paperwork about who my father was. I told them that he had been a well respected goldsmith and that he was falsely accused of speaking up against the Stalin and taken away, jailed and murdered. It was 1954, I came back and the officer looked down at me and told me to get the hell out, that sons of “enemies of the communist state” were not welcome at the college. I was heartbroken, I cried, it wasn’t fair. I was forced to grow up without a father because of a lie someone told and now it was preventing me from pursuing my dream. It hurt a lot the first few days, then I saw my mother. She said “you draw and you sculpt, go enrol in an art academy”. So I went to the Azim Zadeh Art Academy , I showed them my sculptures and my drawings and they accepted me. I saw a group of young artists getting together and sketching in the evenings, I tried to join them and they told me to get the hell out of there because they thought I wasn’t a good enough artist. I went home that day and from that day forth I started drawing everything, portraits, kettles, fruit, tables, chairs, spoons, every guest who walked into our home. I wanted to be good enough, I wanted to be better than they were. A year passed. I was fourteen years old and I returned to that club and they accepted me, they were so impressed by how much I had grown as an artist. Four years later I got my diploma, the four of us got into a train and went to Moscow to apply to Surikov University, the most prestigious and hard to get into art university in that part of the world to this day. I was nineteen years old. Two of us made it, it was 1959. From all the republics of the USSR they chose only 20 students, and I was one of them. This is how I started my formal education to become a sculptor. I studied at Surikov for six years. We had to learn anatomy and draw, a lot. Eight hours a day every day except for the weekends. They would bring kadavres into the studio and we had to sketch muscles, bones, joints, to understand how the anatomy of the human body works before we could sculpt it. We did life drawing, sculpted nudes. We had phenomenal professors. They were all professional sculptors and artists. For the first two years that I lived in Moscow I didn’t know the city at all. Every day I would arrive at the university at 9:45am and leave at 10pm at night. On Saturdays and Sundays we were obligated to go to military college as part of our studies. We would go to the outskirts of the city in a small bus and learn strategy and tactical, weapons. Our commander would spread out a map and discuss military strategy. I’d be a joker and take a little tank out of my pocket that i had sculpted out of plasticine and throw it onto the map. “Look, the Soviets are attacking!”. He would get angry with me and tell me to put it away. Then two minutes later I’d produce another little sculpture, this time a bomber, I was very fast at sculpting. Finally, he said “Rakhmanov, you have to stop this, this is serious, you’ll get expelled”. we were taught to clean pistols, machine guns. Two years later they stopped the course and I started having more free time. But during those first two years we were studying seven days a week.

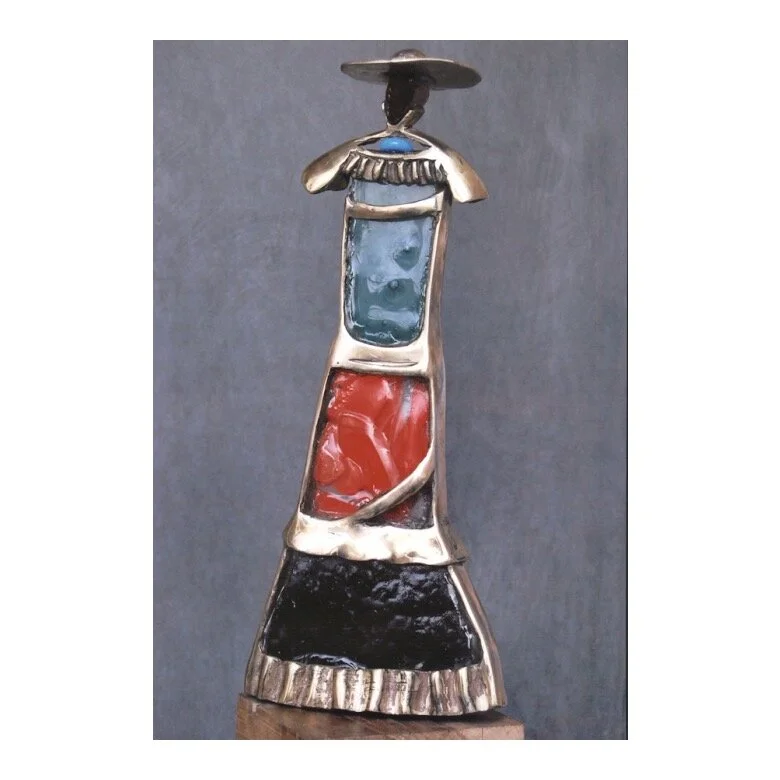

‘Spanish Woman’ / Bronze, Glass

‘Angel’ / Bronze, Glass

What makes sculpture and art so vital for our society in your eyes?

All civilizations in the history of mankind wished to create opportunities for making art because art is one of the driving forces of intellectual evolution. It has a compassionate nature. It’s not military or feudal. It’s rare for a government authority to create opportunities to make art, to write literature, to create sculpture. Humanity is like river water, it comes, it goes, it flows, it disappears. What will be left when we are gone? I respect archeologists, because they uncover what was. And it’s all us! But it’s us a thousand, two thousand years ago, and what will be uncovered of us a thousand years from now? I believe that humanity shouldn’t evolve itself through politics or militant effort, it should evolve through art, through, literature, through sculpture. Every civilization of the past, the Egyptians, the Romans, the Ancient Greeks, have left us something fascinating to look at and interpret. Some of it we can’t even comprehend. How were the pyramids built? Creative evolution gives us an opportunity to be proud of humanity, for all the great art which was accomplished throughout the ages. For me as a sculptor it is of the outmost importance.

What have been been some of the biggest challenges that you have encountered on your path as a sculptor and how have you overcome them?

I’m going to spare you the trouble of hearing about all the technical challenges which come with making sculpture which have to do with power tools and casting. One of the biggest challenges is to sculpt an idea in a way that you can translate the philosophy and the language behind it to the audience. I studied philosophy on my own time. I always aim to create sculptures which speak of more than what we see with our eyes. To create depth. There is a thought process which comes into play before the physical creation of a composition. How will it look 3D, 4D, top, bottom, size, how long it will take to create? You need to master the knowledge about the materials you work with. I spent the first half of my life and career gathering this knowledge. I had been sculpting since the age of five and only when I turned forty did I become completely confident in the realisation of my ideas. You also have to be prepared to face the fact that not everyone will understand your sculpture, this one or the next one. Not everyone is prepared for this way of thinking. I told you before, everyone observes, but rarely does one truly see. These are two different things. Only the one who thinks, truly sees. Most of us observe, most of what we observe is largely useless.

‘Meditation’ / Bronze, Stone

‘Memories of Mother’ / Bronze, Glass, Stone

Why do you think you have such a love for sculpture as a form of expression?

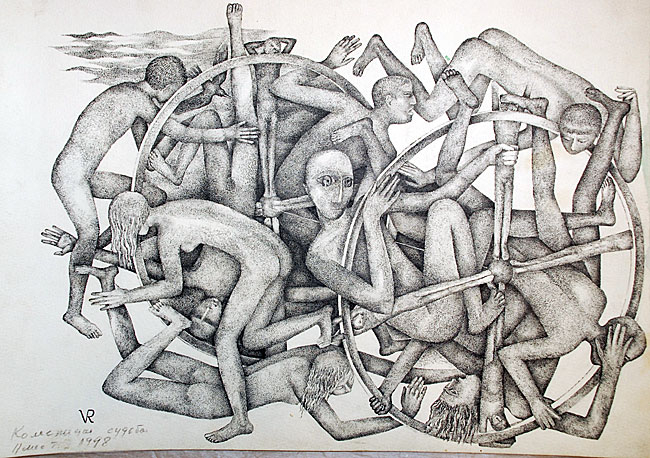

I have been asked this very question by many journalists throughout my career. Sculpture is familiar to me on a very intimate level, because I started when I was just a child. It has been with me my whole life and the more time passes, the more it helps me answer certain questions which I have been searching to answer all my life, or questions which life creates. For example, when you were little, I made a chariot series. One is in a park in Ukraine, one is in Bulgaria, they are all different. Some are smaller. I was representing an era in human history. It’s not that man just got onto a chariot and went on his way. The chariot is representative of an evolution taking place, it’s the main engine so to speak. It represented a philosophy. Sculpture has been there for me always and life is never boring. When I’m in a train or a plane or in a car, what do I think about? I always think about sculpture, new compositions, new ideas. It’s like family to me, that is why I love it, especially when I am able to create the sculpture I have envisioned.

Can you talk a little bit about your process? How is a bronze sculpture made, from inception to the final product?

I have almost always collaborated with a moldmaker to cast my sculpture into bronze and once the casting was finished I would pick it up, cut the framework, clean it up, spend days to weeks polishing with power tools. When I came to Canada in my 60s I went to a casting workshop and learned the process myself. I make my bronze sculptures using the lost wax technique. It’s centuries old. The term derives from the melting of the original wax model out of the created investment - to receive the bronze sculpture. I buy my wax mostly from bee farmers, take it to the studio, heat the wax up in pots and add a softening agent, about 15% of the wax mass. The wax has to completely melt but you can’t leave it to boil because it can set everything on fire. Once the wax has melted and been successfully mixed with the softening agent I pour it onto sheets of metal on the floor to cool and harden. Then I store it in boxes and use it to sculpt. I keep unfinished sculptures in the refrigerator to protect their form. When a sculpture is done I drive it to the foundry where a fiberglass and gypsum mold is created around it, with framework to keep the wax from sticking to the gypsum. When the mold is finished, melted bronze is poured into the cast at 1150 C and left to cool for 24hrs, longer depending on the size of the sculpture. Once the casting process is over I drive to the foundry and crack open the old with a hammer to reveal the raw sculpture. After the sculpture is picked up from the foundry it looks nothing like the final product, you have to clean it up, cut bits and pieces of the framework off with power tools, and start the polishing process which can take a very long time. That is the traditional way. Sometimes the foundry makes mistakes, molds can break, and models which took weeks or even months to sculpt can melt away leaving you with nothing. It’s a long and scrupulous process.

‘ Reflection II’ / Bronze, Glass

‘Silhouette’ / Bronze, Glass

What is your favorite medium to work in and why?

It is quite rare for a sculptor to work well with multiple mediums because each one commands a depth of knowledge. I was always fascinated with the capabilities of different materials, and if I had to choose my top two it would be limestone and bronze. There are compositions you cannot execute in limestone and there isn’t always an opportunity to cast bronze. When I sculpted monumental works I preferred limestone. It offers the opportunity to create large scale works - 2, 3 meters and larger. Bronze has limitations in that sense because you need a team of assistants to create something out of bronze which is on that scale. Limestone gives me an opportunity to create the sculpture from start to finish on my own. Bronze has many steps and the casting is done in a foundry by a trained technician. Now, while I have access to bronze and the foundry, I prefer bronze. Bronze permits you to do things stone does not allow. The techniques are completely different.

Can you talk about the evolution of your style and what triggered you to start using bronze and glass together?

I thought about it for a long time. Why did I one day start mixing bronze and glass together in sculpture? And I got to the bottom of it. I flew to Baku to visit my now late sister Maral, and she said to me “you know, our grandfather was a stained glass master”. He created incredible ornamental stained glass. So I though, remarkable, it came through genetic inspiration without me even realising it. The first time I had the idea I was in a stained glass studio in a large warehouse. They had just finished a monumental project there and I saw that all the scrap glass was thrown out in the corner. After everyone left, I instinctively went and picked up two boxes worth of glass fragments and took them to my car. For what exactly, I did not yet know. It was automatic. Only a few months later as I was sitting at my studio in Almaty, I was looking at these fragments and wondered what it would be like to incorporate them into sculpture. In that moment I believe my genes took over and that is how it all began. Colored glass is hard to come by in Kazakhstan, especially red and orange. I bought a specialised oven and started collecting and melting glass. I realised that Heineken bottles and Borjomi water bottles melted created really wonderful looking colored glass. The colors I could find on the market, I bought. I started creating sculptures out of bronze and glass. No one we found, did it at the time. I had your older sister research bronze and glass sculpture and the only results we found were more decorative pieces, furniture, decorations. I fell in love with the combination of these two materials, bronze and glass.

‘Mountain Woman’ / Bronze, Glass

‘Merging’ / Bronze, Stone

What is the meaning of life according to Vagif Rakhmanov?

I love philosophy so I often ask people, what is your purpose, why did you come to this planet? It’s funny that we know so much, physics, mathematics, history, philosophy, chemistry but we don’t know what we are doing here exactly, on planet earth. Physics tell us that there is a reason for every movement in this universe. So we come face to face with consequences of those movements, but as to what the cause is, we seldom stop to think, we have no time. What are the reasons? To get the answers to the questions you have to know history, especially the history of art, because only the history of art can shed light on humanity which came before us. Some people disagree with Darwin and say that we are all extraterrestrial beings. I speak of my meaning through sculpture. Journalists over the years have been able to understand that most of my compositions have to do with the essence and themes of love. Love is something which stays with a person from birth until death. I believe that we as human beings must honour our very essence, which is love, great love. To understand that the opposite of love, which is anger and hate, is non harmonious with our very essence. Only love makes things grow. A flower blooms out of love. In my life and sculpture I honour the highest most beautiful emotion which mankind is capable of experiencing, which is love.

What advice would you give someone studying to become a sculptor?

When I used to teach sculpture at the Academy I would ask my new students, “Are you all sane?” They would all of course say “Yes'“, and I would then turn around tell them “Ok, then I’m going to go because you’re never going to make great artists”. They looked at me in shock. I would then explain that an artist is an individual who has the ability to not only observe, but truly SEE. There is a big difference. To look at versus to see, there’s a huge difference. Because an artist looks to interpret and depict, not necessarily to execute photorealism. For example, I would search for a personal interpretation of Jesus. There are no photos of Jesus but the depiction of Jesus is everywhere. How is this possible? It’s an interpretation, created by artists which has been adapted in various forms of art, so that is what Jesus looks like today. No one really says “Hey, that’s not what Jesus looks like”, because the depiction has become universally accepted.

If we talk about serious sculptors, on average they are better at drawing then visual artists. Why? Because sculptors either intuitively or are trained to see and deal with interpretation and depiction of a 3D object whereas painters for example only need to see one side of something.

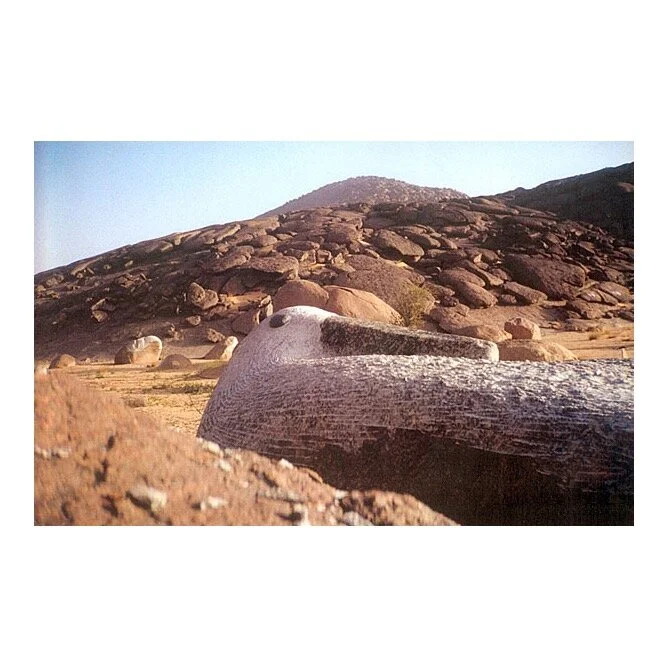

‘Petrel’ / Granite / Mauritania Symposium

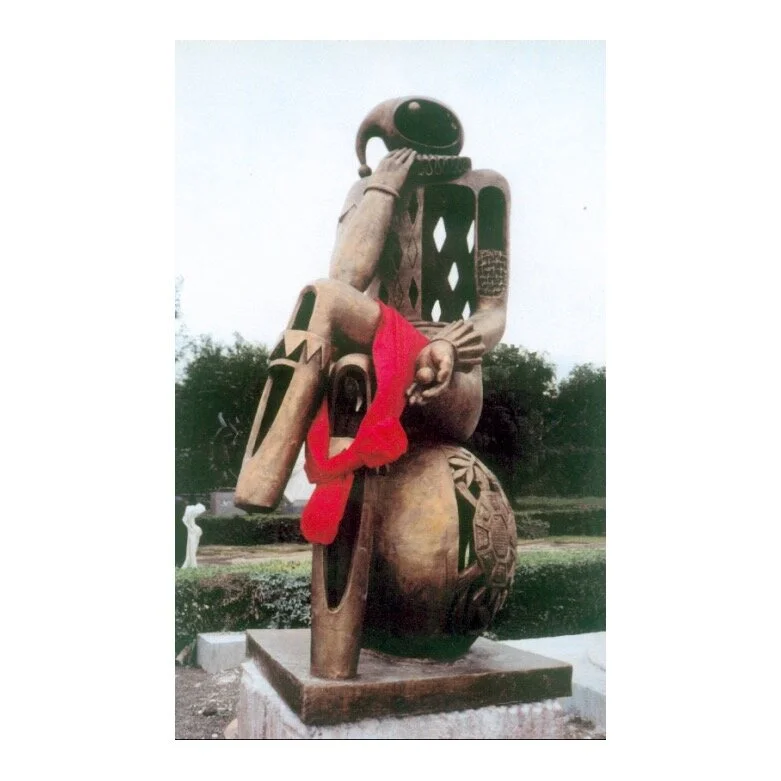

‘Artist’ / Bronze Monument / Changchun, China Symposium

What are your feelings regarding how sculpture has changed over the decades of your life? In your day and age sculptors had to be classically trained for years to be considered competent and to be accepted as masters. In today’s age many individuals call themselves sculptors without having any formal training or understanding of materials and craftsmanship.

I read a lot. My brain works in a bit of a different way than my colleagues. I read a lot because I understand that I need knowledge, knowledge of music, literature: French, Italian, English. I make it my business to know about the driving forces and trends behind other forms of expression. I ask myself, what are people of the 20th century interested in seeing? What new information and forms of expression has the youth of today cultivated and I think about it and weigh it against the more classical understanding of art and sculpture. We need to change and evolve. My colleague asked me, how do you manage to stay current as a sculptor, you were born in 1941, but you are contemporary. I told him that you have to be aware of everything and its evolution: music, literature, social trends, even astronomy. I was always surprised how people seem to have this propensity for having a one track mind, choose to focus on one thing, talk about one subject, have narrow interests. As a student I understood that I always needed new information in order to grow as an artist. What resonates with the modern day audience? At the time it was monumental style park sculpture - but that was the 1960s. You have to respect your craft and in sculpture that means you have to have a level of education. It’s a serious artform, it has to be treated as such.

‘Dante’ / Bronze / Toronto, Canada

‘Chariot’ / Marble, Limestone / Burgas, Bulgaria

Name three qualities which in your opinion make a great sculptor.

There are many qualities that make a great sculptor but if I were to narrow it down I would say: first what separates a sculptor from the masses is attention. The ability to pay attention to everything around you, people, environment, details. Today your subject matter may be a beautiful woman or a handsome man, tomorrow it may be a goat or a horse or a bird, tree, whatever. You need to pay attention to everything, specifically attention to form. To add to this, all every piece of knowledge which has to do with that particular sculpture, you have to be well educated on: drawing, composition, inordinary ways of thinking, understanding of philosophy to some extent. You have to put in effort, hard work. The ability to work very hard for your art. For a real artist, it’s not about ego. Patience is a big one. You cant ever expect that you will create something and the world will stop to give you accolades. Only time can recognize a great work of art. Some sculptures take weeks, some take years to create. You need to have the patience to take your artwork to the state that you have envisioned for it as its creator. It’s sculpture, it can take ten years to create, who knows. A colleague of mine had started a sculpture before the war, a nine meter rider on horseback. He went away to the front, then came back and worked on it for five more years. I was there when he was inaugurated into the National Academy of Arts with a gold medal. It was a great moment to witness. All these qualities are very important, but especially patience. Even if a sculptor wants fame. For a real sculptor, recognition doesn’t come during your youth because you need to show yourself, really show yourself as a master. No one knows how long that will take. In my circles, the pessimists say “fame knocks on your door right before death is about to arrive” haha. Something like that. It’s a matter of luck I guess, if you have time left to enjoy the recognition and the respect that comes with decades of mastery.

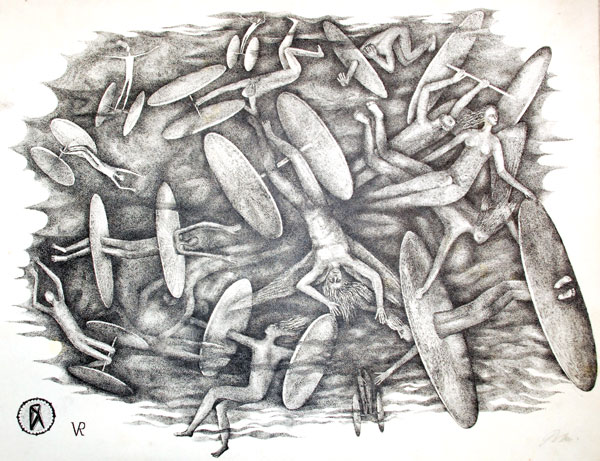

Chariots II / Ink on paper

Chariots of Fortune / Ink on paper

You have been living an extraordinary life. What do you think are some of the keys to living an extraordinary life, no matter what profession you are in?

Self realisation is key. The opportunity to realise oneself, if what you do is needed by society. All people should be able to do what they love, Unfortunately we still live in a world which has degenerate ideals. Otherwise there would be many people who love their lives and what they do. A large chunk of humanity - all they do is work day in and day out to feed themselves. It’s wrong. It speaks volumes about how wrong our society is. People should be raised, from childhood to do what they love. You love music? Do that. Imagine how many creatives are lost because they have to feed themselves and their families. They are forced to work in industries they don’t care about because they are living to survive. And much of this is thanks to the governments, who always find ways to incite war and conflict, to conquer each other, all at the expense of the people. Even people like Alexander the Great, did he have a bad life? No. But he needed to go and conquer. So did Napoleon. What was Hitler’s problem? Why couldn’t he just live as a contributing member to a compassionate society? I am just bringing up examples of how there’s this need for conflict and war at the top echelons of society. The sales of weapons is a multi billion dollar business. War is a multi-billion dollar business. Life is short and I believe that we need to be creative, we need to create art. This also touches upon another problem. Many artists cannot support themselves creating art because society doesn’t value art. Society only starts valuing some art after the artist dies. We need to reevaluate our priorities and our value systems.

‘TFN Talks’ In Partnership with Tropical Nomad Coworking Space